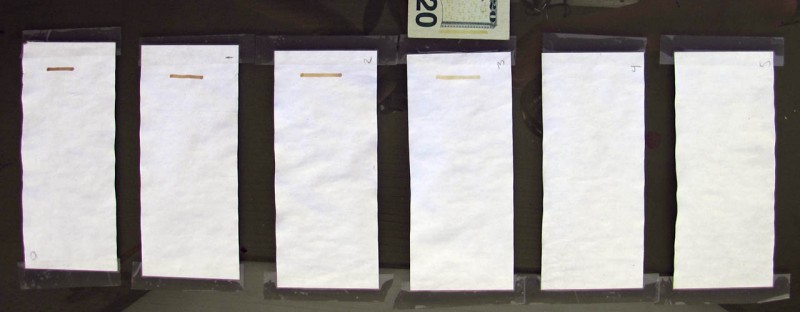

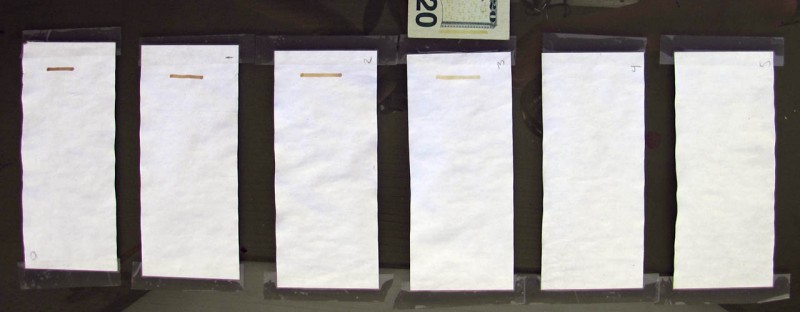

From left to right, test sheets have been treated with 0.000, 0.007, 0.015, 0.030, 0.060, and 0.120 M ascorbic acid from ground vitamin pills, allowed to dry, ad marked with a counterfeit test pen. The 0.030 M solution produces a stable color that is very close to the mark on a real US $20 note, top. That color only becomes stable after about 30 seconds, however, and the visible color change over time is not seen on authentic bills.

Well, sort of.

Some time ago, a friend reported to me a rumor he’d heard that Aqua Net hairspray could be applied to regular paper to defeat a counterfeit test pen. I tested it, and found it wasn’t true, at least not with the kind of Aqua Net I used. But in the course of reading up to perform that test I learned that counterfeit test pens work by the common starch-iodine reaction: Iodine and starch create a complex species that has a distinct blue-black color. Currency paper has no starch in it, whereas most common paper does. So if your paper turns blue on exposure to iodine that’s a pretty good sign it isn’t real currency paper. That, or some jerk has treated your real money with spray-on laundry starch which (though I haven’t tested this, yet), would probably make real currency paper test as counterfeit.

Anyway, so I knew from that little experiment how the pens work, and when a buddy at MAKE recently rehashed our invisible inkjet printer project from Vol 16, I realized that the chemistry in use there, in which vitamin C inhibits the starch-iodine reaction to develop an invisible ink, might well imply that a solution of vitamin C would also defeat the same reaction when it’s used in a counterfeit test pen.

Turns out I was kind of right. Just kind of. A 0.030 M solution of vitamin C (ascorbic acid) made from ground-up vitamin supplements gives the counterfeit pen a stable color on normal office copy paper that is hard to distinguish, visually, from the color of the pen on a real banknote. Trouble is, it takes awhile to reach that stable color. Like 30 to 45 seconds. It’s darker, at first, and then fades. Stronger solutions of vitamin C make the mark fade more rapidly and to a lighter color than is “correct,” whereas weaker solutions do not fade the mark as much and leave a darker color than is “correct.” Specific experimental details are in small print below.

So, it appears to me that vitamin C does not actually “inhibit” the starch-iodine reaction; rather, it out-competes it energetically. The product of the reaction of vitamin C with iodine is, I think, more stable than the starch-iodine complex, but the starch-iodine complex forms faster. So you get a visibly dark starch-iodine reaction which fades to a lighter color as the iodine is drawn off to react with vitamin C.

10 x 1000mg vitamin C tablets were ground in a mortar and pestle and stirred overnight with 2 cups carbon-filtered tap water to prepare a 0.120 M solution of ascorbic acid (and possibly other pill ingredients that have not been identified or controlled for). Serial dilution produced solutions of 0.060, 0.030, 0.015, and 0.007 M concentrations. Water from the same source was used as a control. Bill-sized pieces of Office Depot copy paper were cut, rolled, and each soaked overnight in a test tube containing one of the six test solutions. The next day, the rolled papers were removed from the test tubes, unrolled by hand, and couched on separate folded paper towels to dry overnight. They were then taped to a piece of plate glass and an approximately 1-inch mark was applied using a commercial counterfeit test marker. A new US $20 note was also marked for comparison. The samples were photographed immediately, and after one-half hour. The samples were marked again, and each mark filmed to record the first 30 seconds of the color reaction’s time course. The 0.030 M solution was found to give stable color that very closely matched the marked reference bill by visual inspection. Weaker solutions gave darker marks that were not deceptive, and stronger solutions gave faint or completely absent marks.